Intel Corporation - Part 2

How much should we pay for this company

Last week we had a look at Intel, a semiconductor designer and manufacturer that has had a dominant position in the industry over the past 10 years, but which has been out of favor in the more recent past.

We’re going to be doing some calculations, and seeing some ways to value the company.

The Valuation Methods

Intel is a different company from the ones we have been discussing up until now, these differences were made obvious last week when we had a look at its overall revenue and net income growth over the past 10 years.

Unlike Aflac or 3M, who had flat revenues over the past 10 years, Intel is clearly a growth stock that has been meaningfully growing their business. In addition, Intel is in a very cyclical industry, and one in which R&D is a major part of both expenses as well as being able to compete in the industry.

This means that our previous methods of valuation might not be as useful as others.

That said, let’s go through the following valuation methods, some old, and some new:

Profit Margin to PE Method

Benjamin Grahams formula

Discounted Cash Flow

Net Current Asset Value

Peter Lynchs Growth at a Reasonable Price

Some of these we’ve seen before so we won’t spend too much time on how to calculate them. If you want to see the formulas and a more in depth discussion on them, check out Part 2 of my Aflac Deep Dive.

Here’s the table showcasing the current value estimated by each of those first 4 valuation methods:

Overall it looks pretty positive, the major jump between the 10 year Average and the 2020 value is the result of the increase in earnings over the past 10 years which is a good thing to see in a company.

The estimated value for each of these methods of valuation are all roughly the same, which is also encouraging.

I would say the real value estimated here is closer to $80 to $90 than the 10 year average or the Discounted Cash flows, but in either case I think we can set a minimum value of around $75.

Out of curiosity, let’s check the profitability of it’s core competitor, AMD, using the Margin method:

Well that looks strange.

If we use only the 2020 data (using averages of the past 10 years is even worse for AMD), we can see that the expected value of Intel is around $158, whereas AMD is at a paltry $26.

Even if we were to use Intel margins for AMD (assuming for example that they would command an equally dominant position as Intel as had), their per share price should only be around $66, well below its current market price.

AMD has significantly lower margins as well as lower EPS, and yet it commands a significantly higher price per share right now.

While it’s true that AMD has jumped ahead of Intel in the past couple of years, it feels like the market is already valuing them with the assumption that they are the dominant force in the market, when that is not yet the case.

I can’t help but feel that AMD is either wildly overvalued, or Intel is wildly undervalued.

Let’s talk more about this next week.

Growth at a Reasonable Price Method

Growth at a Reasonable Price (GARP) is an equity investment strategy that seeks to combine the tenets of growth investing and value investing to select individual stocks.

GARP investors look for companies that show consistent earnings growth that is above the broad market levels, while excluding companies with overly pricey valuations.

This investment strategy was popularized by Peter Lynch, and while he did not set exact parameters for his valuation, in general the idea is to invest in stocks that have a PEG at attractive levels.

A price-earnings ratio lower than the earnings growth is considered normal, and the lower it goes the more attractive it is, while ratios above 2.0 are considered unattractive.

Lynch refines this measure by adding the dividend yield to earnings growth.

This adjustment acknowledges the contribution that dividends make to an investor’s return. The ratio is calculated by dividing the price-earnings ratio by the sum of the earnings growth rate and the dividend yield. With this modified technique, ratios above 1.0 are considered poor, while ratios below 0.5 are considered attractive.

We can calculate these ratios for Intel right now:

Intel is not too particularly undervalued, but also not overvalued.

However we should be able to use these rules of thumb to generate a value at which it is worthwhile to purchase the company, we just need to do some algebra.

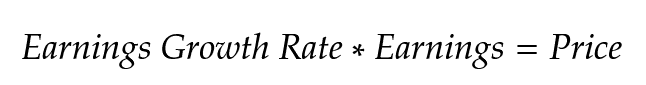

In short, we have 2 possible formulas:

and

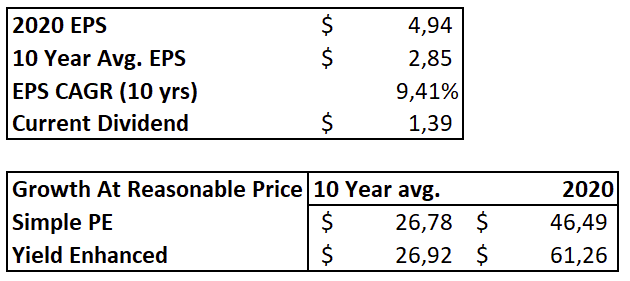

We can now use those formulas to derive the threshold value of Intel based on their earnings, and growth rate.

For the first formula:

And for the second formula:

You may notice an issue with the second formula, after all, the yield of a stock is dependent of its price, so making the price dependent on the yield will simply make a circular reference…

In order to resolve this issue I will use the price indicated by the first formula as the divisor to calculate the Yield. It’s not a perfect solution, but it’s a simple enough way to calculate it.

Wow!

Those numbers are looking significantly lower than our previous estimates!

What’s up with that?

Well, the Growth at a Reasonable Price method is meant for super high growth companies that are growing their earnings 20+% every year.

As you can imagine growing earnings that much for 10 years is quite difficult, so Intel has “only” managed a comparatively paltry 9.41% CAGR.

That said… What happens if we just use the last 5 years as our baseline for the growth rate?

That’s a pretty big difference, the value estimated is almost twice as much, and much closer to our previous estimates!

Is this a good valuation method?

I don’t think that the Peter Lynch Growth at a Reasonable Price rule of thumb can create a good formula to determine the price you should pay for a company.

While it is a fairly decent litmus test to check if a growth company is at a given moment undervalued, I think it leaves a lot to be desired for a valuation method.

For one it puts a lot of emphasis on earnings growth, which is a good thing since most returns come from earnings growth, however the dividend yield also plays a significant part that isn’t explored (other than in the yield enhanced model, which has its own issues).

Furthermore cyclical industries are not well represented here, since often periods of low growth are succeeded by high growth periods. This naturally results in wildly different valuations depending on when your cut off time is, as we can see here with Intel.

It also has issues when it comes to valuing unprofitable companies that nevertheless might become wildly profitable in the future.

Overall I think it might be worthwhile to explore ways we can value growth companies, but that will have to be left to a later post.

Summary

Overall I think the true value of Intel is closer to the 10 year average for the Margin to PE method. That leaves it around a very comfortable $80 to $90 per share, which already includes the regular fluctuations involved with this cyclical industry.

Now Intel has been a dominant company over the past 10 years, which might bias the results.

That being said let’s discuss the future of the semiconductor market, and the competitors and issues which Intel is facing over the next decade next week where we will develop a story for this company.

Let me know what you think!

And as always, if you have any questions or comments, shoot them on Twitter @TiagoDias_VC or down below!

And of course, don’t forget to subscribe!