Debt Cliffs

A dangerous and little talked issue

In our last few posts we talked about debt cliffs, and particularly mentioned that companies like McDonalds didn’t seem to have any big debt cliffs despite having quite a lot of debt.

Today, we’re going to be talking about debt, bonds, coupons, and debt cliffs, as how they can affect the health of your companies, and introduce bankruptcy risks in otherwise perfectly functional and viable companies.

What is a Bond?

As per Investopedia, a Bond is:

A bond is a fixed-income instrument that represents a loan made by an investor to a borrower (typically corporate or governmental). A bond could be thought of as an I.O.U. between the lender and borrower that includes the details of the loan and its payments. Bonds are used by companies, municipalities, states, and sovereign governments to finance projects and operations. Owners of bonds are debtholders, or creditors, of the issuer.

Bond details include the end date when the principal of the loan is due to be paid to the bond owner and usually include the terms for variable or fixed interest payments made by the borrower.

In other words, a bond is a loan that an investor provides to a company, in return for which the investor will receive some amount of interest payments.

These interest payments can be variable or fixed. If they are variable, they are often the same as a benchmark interest rate, such as EURIBOR, LIBOR, or some other interest rate benchmark.

When the bond expires, the amount lent by the investor is returned to him by the company. This expiration date is set when the bond is issued.

What is a Bond Coupon?

As per The Balance, a Bond Coupon is:

"Bond coupon" is a term for the interest payments made on a bond. It survives as part of investment vernacular even though technology has made the actual coupons obsolete.

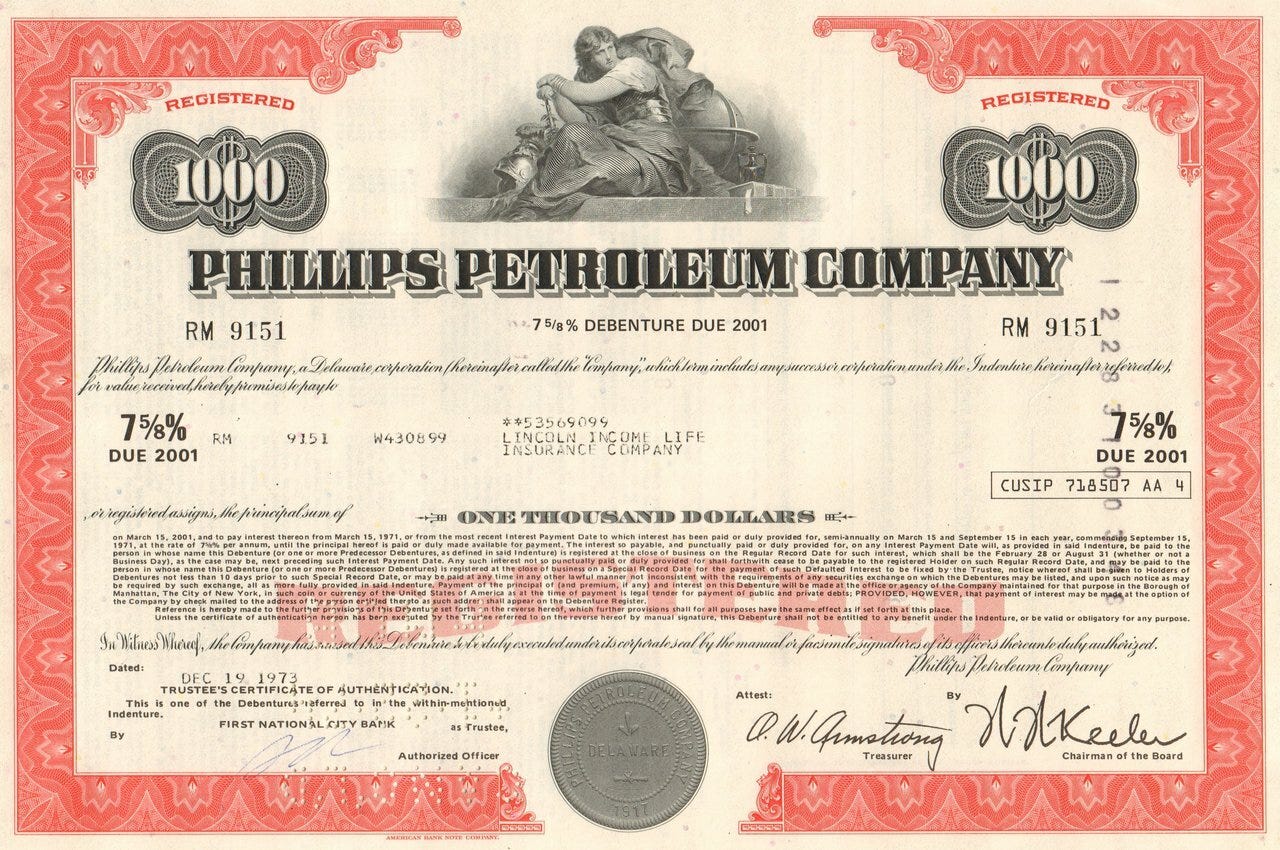

The term comes from the fact that before computers automated and simplified the process, investors who bought bonds were given physical, engraved certificates. These certificates served as proof that an investor had lent money to a bond issuer and that they were entitled to receive the principal plus interest.

Attached to the bond was a series of “Bond Coupons”, each with a date on it. Whenever the interest was due, investors would clip off the appropriate bond coupon and send it to the company, who would in turn send back the corresponding interest payment.

On the maturity date, when a bond principal was due, a bondholder would send the certificate back to the issuer who would then cancel it and return the certificate's par value back to the investor. The bond issue was then retired.

What’s a Debt Cliff?

If you’ve been paying attention to how bonds work, then you might have noticed the problem already, but let me spell it out for you:

When the bond expires, the company must repay the borrowed amount.

This might seem obvious, and it is, but it also has some important implications in terms of capital allocation.

Companies try to ensure that the income generated by the asset they bought using the bond will be enough to cover the interest payments as well as the final cash repayment before the bond expires.

The problem is that having cash sitting on the balance sheet for years, just pilling up waiting for the bond to expire is generally a bad idea.

For one, it’s cash that the company could be using to expand, or pay for its other commitments, without having to go into further debt!

This means companies generally don’t have the cash laying around to pay for the bond repayment upon expiration!

Second of all, is that the final repayment is significantly larger than the simple coupon payments. Indeed, if a company sold a $1000 bond, at 5% interest paid quarterly, the regular payments will be $12.5, but the final payment will be $1000!

That’s 80 times the usual amount!

In that scenario, let’s see what a companies options are here:

Slowly accumulate cash from operations in order to pay off their outstanding bonds

Sell off part of their business near maturity in order to get a stack of cash to pay off their bonds

Refinance their bonds with new bonds with a later maturity

We’ve already discussed why companies might not want to do option 1, and option 2 should be obvious as to why it’s a bad idea.

Option 3 however is very attractive to most companies, since it lets them keep cash off of their balance sheet, and in income producing assets.

The problem that is that this can sometimes cause “Debt Cliffs”, that is, when a company has a lot of bond maturing at around the same time.

Here’s an example for Intel:

In 2022 they have a Debt Cliff where the amounts to be paid in 2022 is about 10 times the amount to be repaid in 2023, and about twice as much as needs to be repaid in 2021.

If the company doesn’t have either the cash-flow or the assets to repay this debt, that is a cash-flow problem.

Intel in this case is just fine, since its free cash-flow is solid, and they have enough assets and expected business to repay this comparatively small cliff, but what if we were talking about a business with less earnings power?

What about a cyclical company where the cliff is located right in the middle of its down-cycle?

Or what if there is nothing wrong with the company at all, but its cash-flows are simply too small to accommodate an unusually large cliff?

In those cases companies often have no choice but to refinance their debt…

But what happens if there is a credit crunch? What if the economy takes a downturn and suddenly they can’t refinance at agreeable interest rates? What if they get their credit rating downgraded by the ratings agencies?

This is the problem with leverage and debt, it’s not that debt is evil and should never be used.

The problem is that using debt adds additional points of failure where one thing going wrong can spiral out of control.

Indeed that’s what happened in 2008!

Companies had to refinance their loans, but due to the housing bubble banks and other lenders were unable to or unwilling to provide the level of financing at the rates that they had done so far. This meant that companies had to refinance at higher rates (if they could at all) with necessarily impacted their growth and day to day operations.

Additionally, the ones that could not refinance went bankrupt, not necessarily because their business was flawed, but because they were over-leveraged at a time where they could not acquire sufficient cash-flow or debt to fulfill their funding obligations.

As investors we need to look out for these situations in companies we own, and stay well away from them!

We don’t want to be placed in a situation where a downturn in credit markets might lead to a disastrous result for the company!

Buyer Beware!

Always look at the debt schedules, not just the total amount of debt, but when it is due to be repaid, and check whether their cash-flows will be able to sustain that, or failing that, ensure that their credit rating and situation is able to sustain whatever refinancing might be required.

What about you? Do you have any other little known factor you take into account in your valuation?

Let me know in the comments down below!

And as always, if you have any questions or comments, shoot them on Twitter @TiagoDias_VC or down below!

I’ll see you next time!